In November 2018, I attended the Compassion and Ethics Summit with his holiness Dalai Lama. During the three-day-summit, I led a short ritual design session with the summit participants. Here are some highlights from this one of a kind summit.

The participants were from diverse backgrounds — including museum leaders, academics, artists, consultants, and designers. They were intentionally invited from different disciplines and walks-of-life to spark creative conversations. The overall theme was finding new and alternative ways to express compassion and ethics in our lives.

Meeting with Dalai Lama

We met Dalai Lama on a sunny, chilly Monday morning after a serene walk from our hotel to the complex where Dalai Lama lives. We were around 30 people. When we got to the meeting, we waited for him to finish his earlier meeting. People enjoyed this waiting time with silence and small conversations. It was also a mental preparation time for most of us, as we all left our smart phones behind, taking in the serene atmosphere. When he finally arrived, people’s silence was broken by bows and excitement.

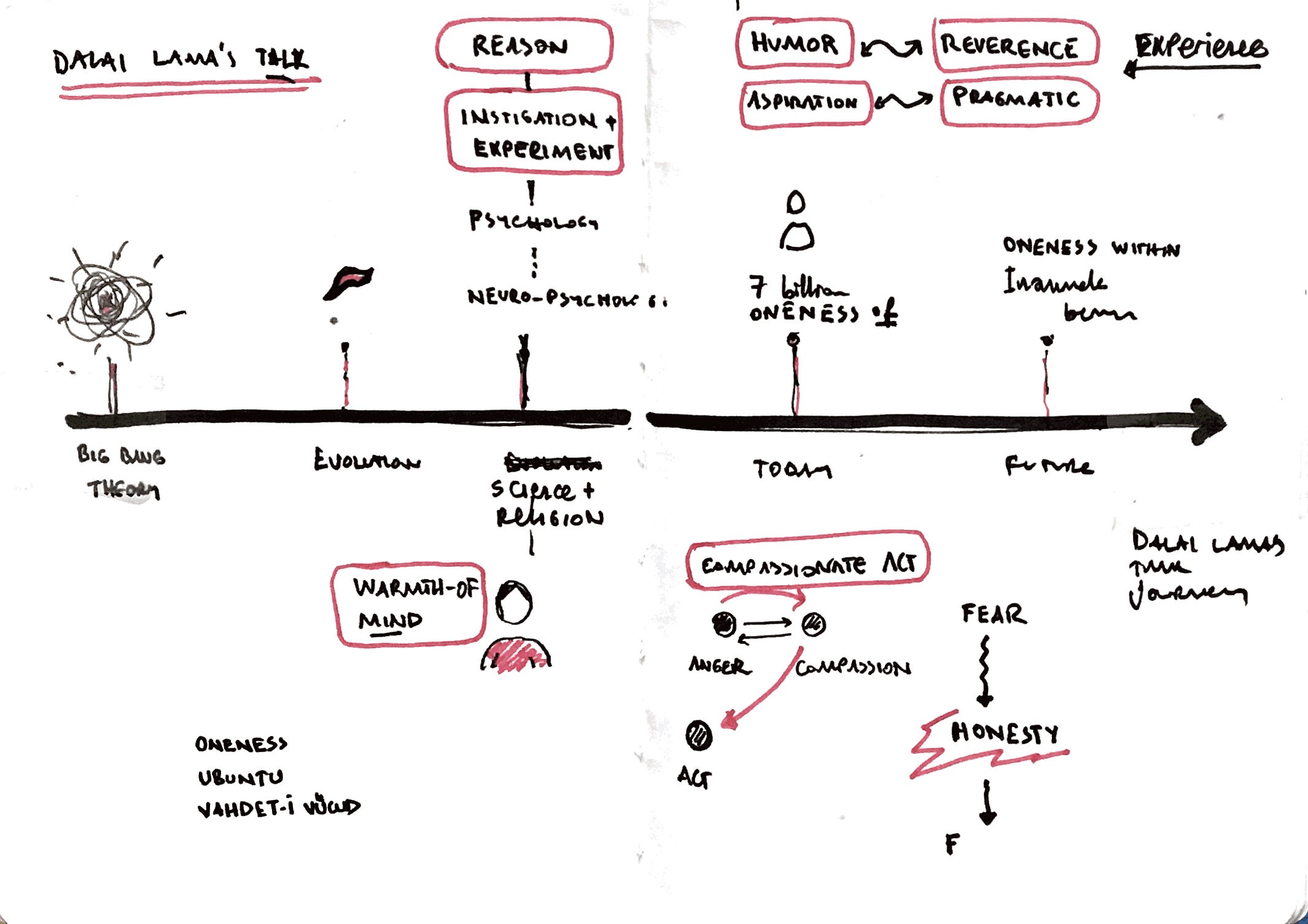

In our meeting, he spoke to us in a journey: taking us from the beginnings of the world (Big Bang theory) to the current times (climate change) with a strong sense of hope for a better world. I drew a map of his talk [see my drawing above] to show the emotional journey through happiness, sadness, awe, hope, and excitement.

And themes emerged from the meeting, and our group’s debrief afterwards. One big theme was the concept of oneness within the world’s pluralism, and another was the warmth of the mind.

On oneness

As the participants come from different faith traditions, there was this strong emphasis on oneness — the oneness of humanity that is built around pluralism of seven billion people. Sufis call this oneness Vahdet-i Vucud, African traditions call this Ubuntu. Dalai Lama emphasized the need to bring this quality through the concept of secular ethics, which relies on common sense and scientific grounding.

On Warmth of Mind

The warmth of the mind was another intriguing concept. Dalai Lama mentioned that there was not a direct concept of warm-heartedness in the Tibetan language. Warm-heartedness is about motivation. It’s the beginning point. The real challenge is about the warmth of the mind, which is about reframing and redirecting the emotions with a positive mind and attitude. He concluded that with the mind (human intelligence) and heart together, you can get to infinite compassion.

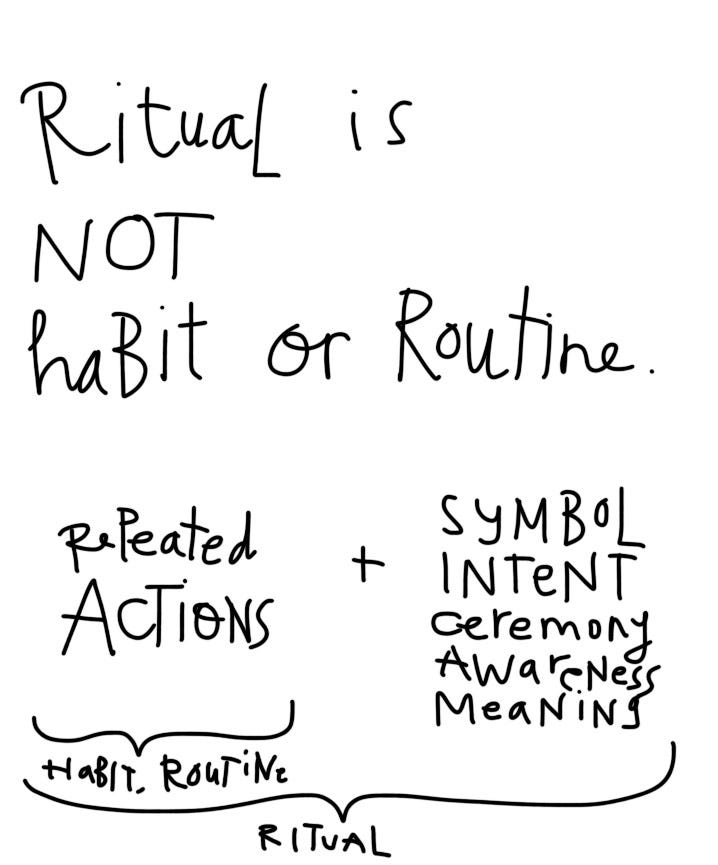

We were impressed by his ability to balance humor and reverence, aspiration and practicality. After the event, we were charged with some kind of positive energy. At Ritual Design Lab, we call this the je ne sais quoi aspect of a ritualistic gathering — where there is an unexplainable emotional energy emerges from the gathering. Randall Collins call this the effervescence effect of rituals.

Designing Rituals for Compassionate Lives

When asked to contribute to the Compassion Summit, we first thought about running an introductory session around rituals. This idea lingered with us for a while. One day, one of us was attending a circuit-training at the gym, and then he had this spark. What if we can practice compassion muscles as if we work out at a gym?

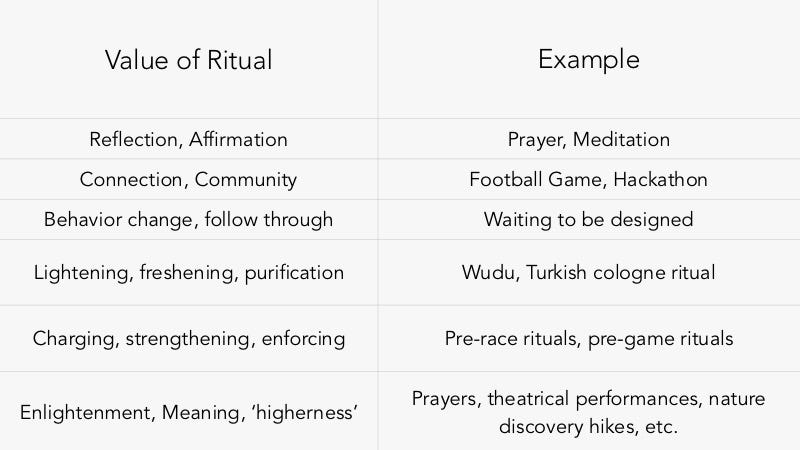

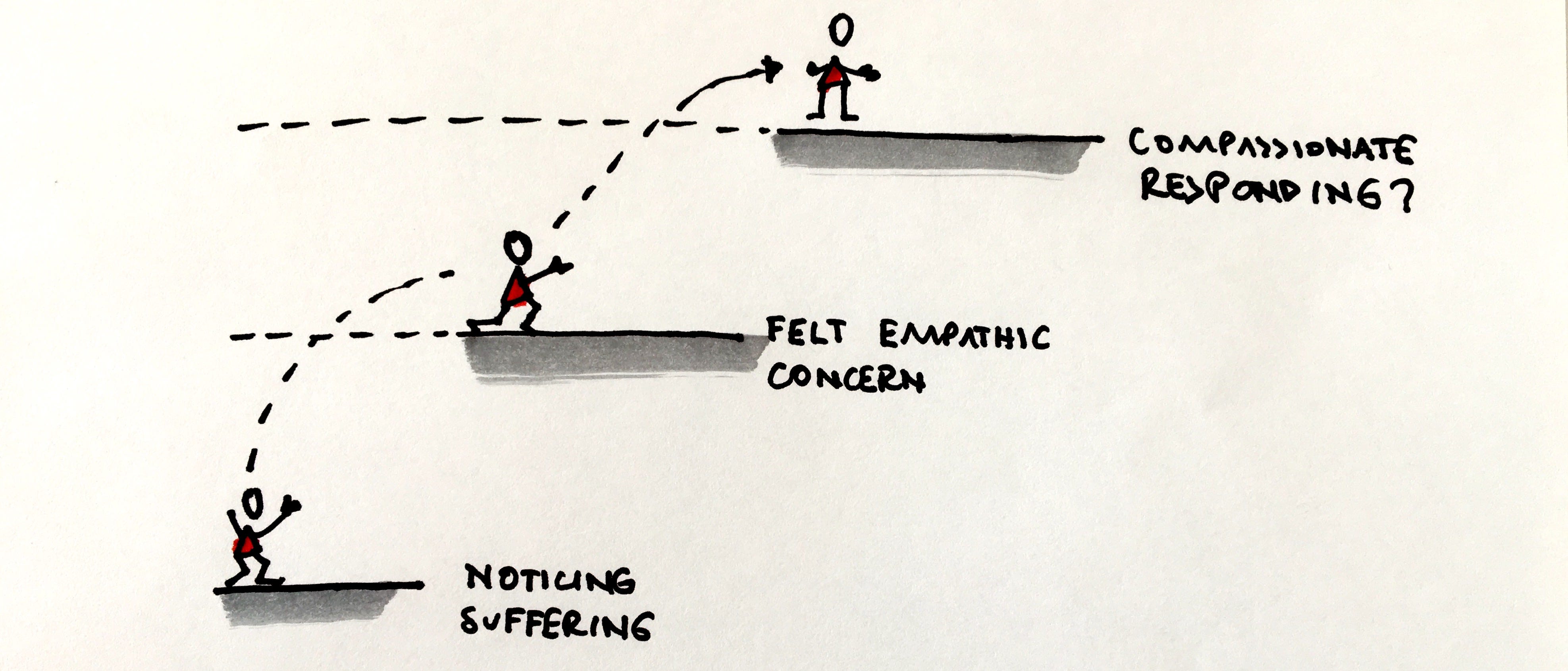

This led us to propose the initial vision for the workshop: designing compassion stations — similar to a circuit-training- for people to perform rituals at a museum setting. We even called it a compassion gym. The journey to the compassionate lives are three-fold, noticing suffering, feeling empathetic concern, and compassionate responding.

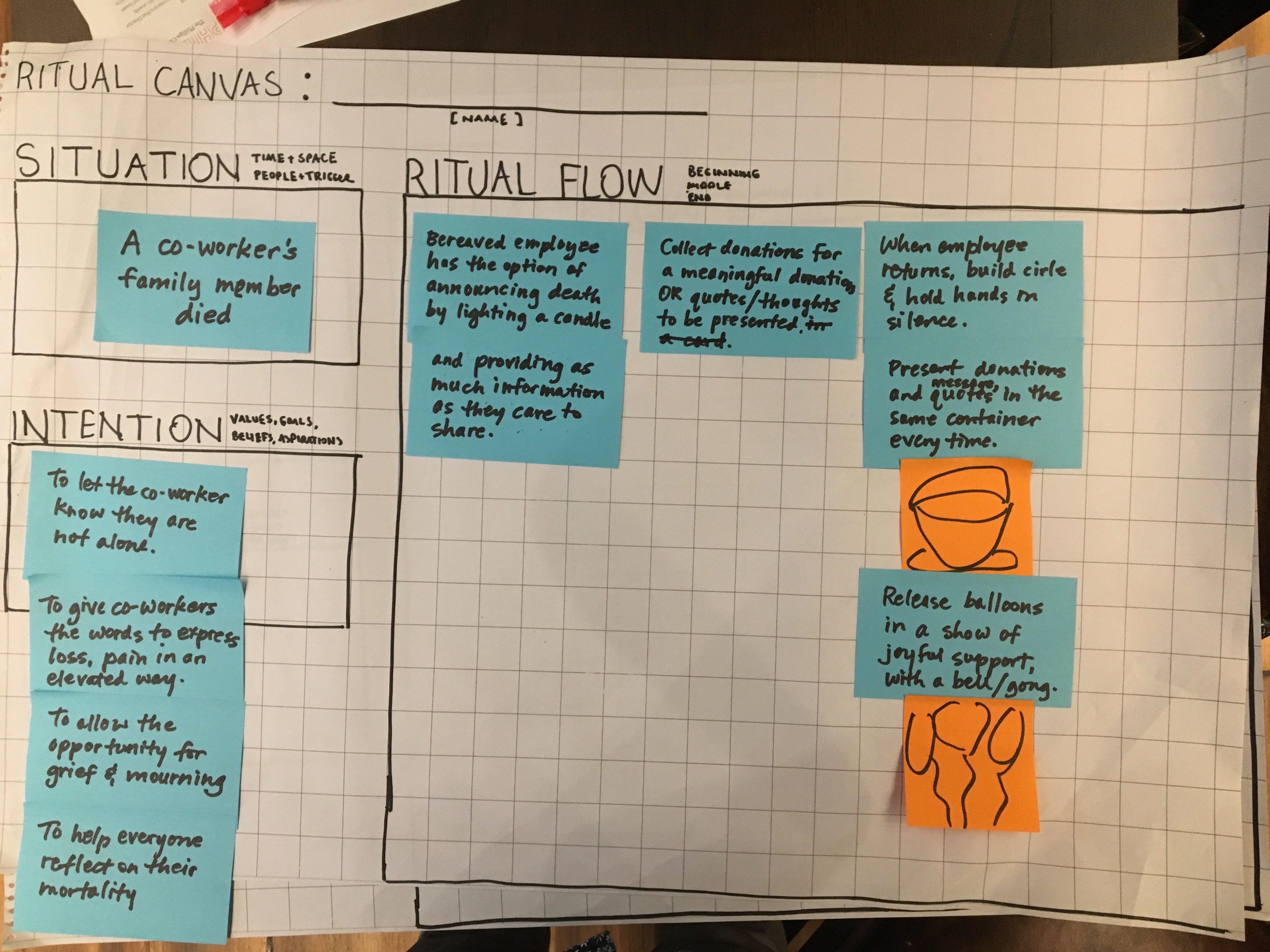

To scaffold this vision, the design challenge was set around how to live more compassionate lives at home, work, and third places. The teams mostly picked work context and prototyped ritual concepts. They picked emotional low points such as returning to work after loss of a close relative. One team performed their mourning ritual where team members recognize the suffering and the loss of their teammate with symbolic acts like the release of balloons.

Compassion gym is still a work-in-progress concept. As Ritual Design Lab, we will be running more experiments on an experienceable ritual station idea. One of our strongest inspirations on this is Exploratorium’s Science of the Sharing exhibition where they managed to prototype social interactions. The idea in Sciences of the Sharing is that our social interactions have a mechanics and can be designed similar to a science experiment.

To recap, the conversations from Dalai Lama and the ritual design sessions get us inspired in multiple ways:

- The size and complexity of compassion challenges don’t matter. What matters is the effort — to change things from an existing state for a better state.

- When you have this agency to make things better, it’s about reframing the existing challenge, and work with mind and heart together.

- Mind and heart are not discrete states of existence. They work in a continuum, with fluidity.

- Rituals can be one of the many toolkits to help people get concrete about compassion.

In the following post, we will highlight several compassion-oriented mindsets and toolkits that the Summit participants shared with the group. These tools invite people to get concrete about empathy and compassion. For designers, they can be exercises and examples for empathy in action, and experience design.

This post is originally published in our Ritual Design Medium publication. Visit to read the other two follow-up posts.